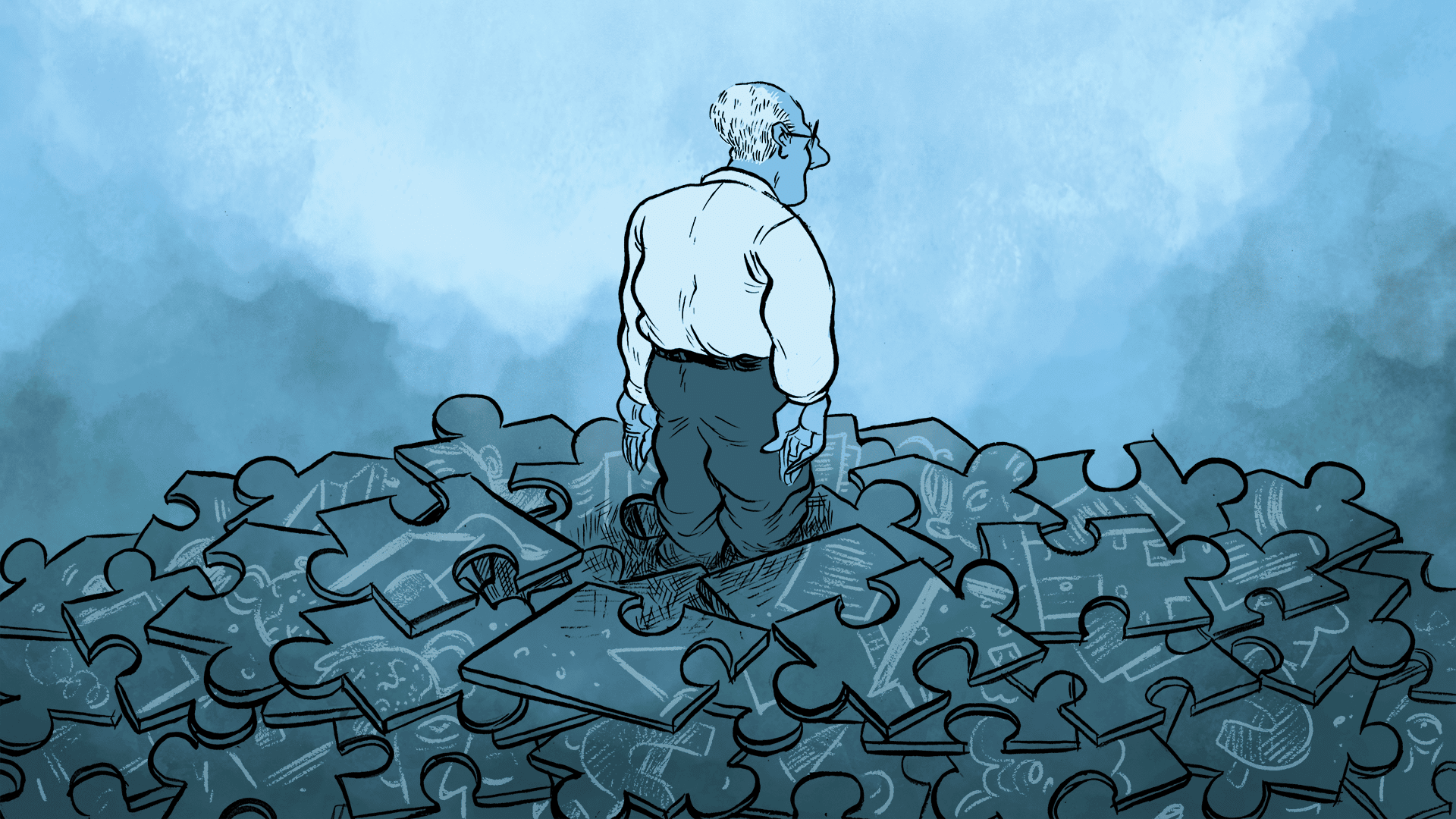

Solving a future puzzle: Managing cognitive decline

Losing mental capacity as you age may also mean losing your chance to make or alter a Will. While dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease can be health tragedies, they may not need to be financial ones if you consider doing your estate planning now.

Susan’s experience with her elderly Aunt Barbie may be a case study of how straightforward finances can slide into disarray. Barbie always had a strong business sense. In her mid-40s, halfway through her career, she left a government position to open and run her own gift shop near a hospital in Toronto. Susan remembers helping her aunt out at the store as a university student over Christmas break. Customers came for specialty gifts, cards and decorations they could only find in her aunt’s shop. When Barbie suffered a seizure in her mid-60s, Susan was named as her aunt’s Power of Attorney (POA) for Personal Care to help look after her aunt because Barbie could no longer manage grocery shopping on her own.

It was only when her aunt began to show more severe signs of dementia, however, that Susan could see more help was needed. She discovered then that her aunt’s estate plans were seriously flawed. Though Barbie had a small pension from her deceased husband and no particular financial complications, she had no Power of Attorney for Property, which prevented Susan from accessing her aunt’s money to fund her care. And she had no Will — at least none that anyone could find.

After her aunt died, Susan had to wade into a financial mess to clean up the estate. Her aunt had been writing exorbitant cheques to her caregiver — yet had not paid any taxes in several years. Aunt Barbie’s estate owed thousands of dollars to the government. What really hurt was that, with the late payment penalty and interest, thousands more that should have gone to her surviving sister, Susan’s mother, instead went to the Canada Revenue Agency.

“It made me sad. My aunt was a strong, capable, independent woman who just wasn’t aware of what could happen if she didn’t make a Will or proper plans. But this was a lesson for my family of what not to do,” Susan says.

We’re all guilty of procrastination at one time or another. Unfortunately, age-related cognitive decline — dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease — may rob us of the opportunity to provide for our families if we put off doing our Wills and other estate plans until it’s too late. But Nicole Ewing says there’s much you can do while you remain healthy that could help lessen the load on the people who care for you.

Ewing, Director, Tax and Estate Planning, Wealth Advisory Services, TD Wealth, says many people naturally put off their Wills until they reach retirement age when transferring wealth to the next generation becomes much more urgent: The problem is, that time is precisely when the risks of cognitive problems begin.1

“An assortment of age-related illnesses can disrupt affairs in a wide variety of ways,” she says. “Fortunately, the solution is straight-forward. Get your Will, POAs and estate plans done early, revisit them often and use professionals to help protect your interests,” she says.

Here’s what you need to know about cognitive decline as you age and how you can take steps to prevent the symptoms from disrupting your finances.

Know these causes and treatments of cognitive decline

Unfortunately, Susan’s experience may become more common. Figures from 2017 show that over a 10-year period (2003 to 2013), the prevalence of dementia increased by 21.2%.2 But the subtle nature of the disease often makes it difficult for people to recognize when their minds may be changing. Slowing down and becoming forgetful is a normal part of aging, but gradually experiencing confusion or having difficulty speaking is not, says Dr. Jeremy Spevick, a neurologist at Cleveland Clinic Canada. This makes it difficult for individuals or families to realize there is a problem and seek treatment.

“I often tell people I see that the problem can be difficult to identify from one moment to the next. There’s a range of behaviours that are normal: There’s often some degree of memory decline that happens to everyone as they age at one end of the spectrum and dementia at the other,” Spevick says. “But there’s a big grey area in between. It’s really hard to tell where you are at one given moment, whether things will stay the same or if the problem is progressing.”

Dr. Spevick says it’s important for everyone to be informed of the risks, causes and treatment for cognitive decline. Although the exact cause for Alzheimer’s Disease remains elusive, management of vascular risk factors has been shown to help reduce cognitive decline. This includes monitoring of high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, inactivity and diabetes.

Not every senior will develop these diseases, he says. But since we are living longer than previous generations, the risks of developing cognitive problems also rise: At age 60, the likelihood of cognitive decline doubles every five years.3 Spevick says the diseases often do not follow a predictable path, which can make a diagnosis hard for doctors and tough on the family involved.

Unfortunately, Alzheimer’s Disease can be progressive and fatal and is a contributing factor in up to 4.3% of all deaths in Canada.4 He says these types of disease are challenging for doctors and effective treatments remain elusive. Current treatments can include Cholinesterase inhibitors but Spevick says unfortunately these drugs can only slow the progress of the disease, not halt or reverse it.

Consider how cognitive decline can impact your estate plans

Ewing says the unpredictability of the disease can cause difficulties for estate and financial planning. She points out that if a lawyer suspects that a client doesn’t have the required legal “capacity” — a definition that can vary depending on the decision in question — the lawyer can’t act on their behalf. This may mean that no Will or POA can be drawn up, or that an existing Will can’t be changed: Altering other legal documents is a long, costly and complicated process and the court may not actually grant permission.

Moreover, she says everyone should consider how cognitive decline can disrupt a person’s life and their family’s lives too. For instance, if an elderly father is showing mild signs of cognitive decline, how might a family react if he wants to make an abrupt change to his legal documents? What happens if family members disagree on the father’s capacity?

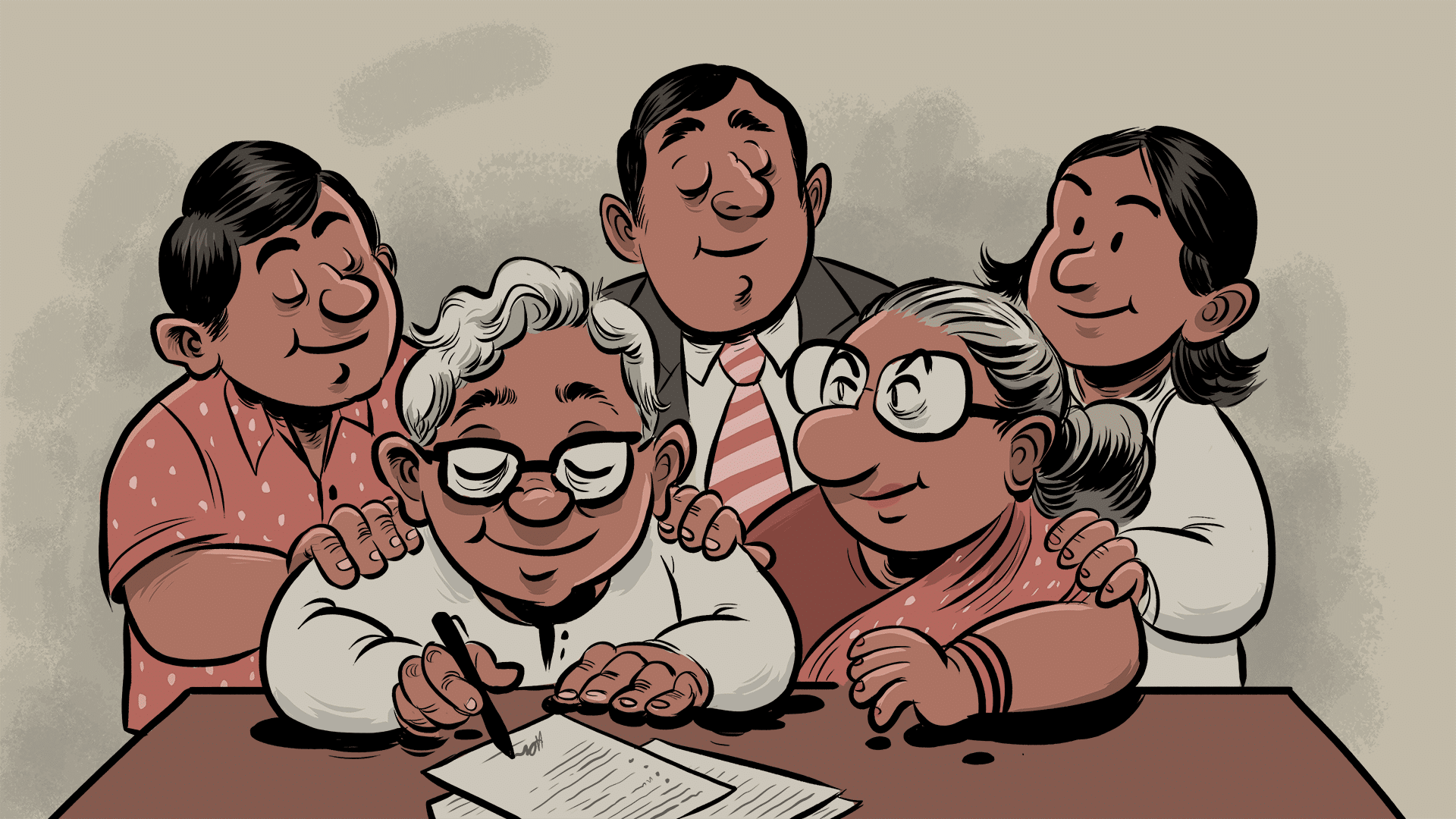

With this in mind, Ewing underscores the urgency for everyone to take action in these three areas to prevent health problems from disrupting their plans.

Do your Will and POAs when you’re young and healthy

Having estate plans and documents completed early in life means your intentions for your wealth are fully lawful should you become incapacitated or pass away. The POA gives the “Attorney” the power to manage your money and affairs for your benefit if you become infirm. And with a Will in place, your wealth should be distributed to the ones you want in an efficient manner.

Not having these documents in place can mean trips to court, legal fees and delays for your family or your heirs, Ewing says. If you don’t have a POA and you’re unable to make decisions about your life, things become complicated. For example, if you require enhanced healthcare and no one can access your money, you can imagine the challenge this may present.

Revisit your estate plans (and let others do it if you can’t)

Ewing tells a cautionary tale involving a father who developed a comprehensive estate plan for his wealth and for his grown children, but which eventually became outdated as tax laws changed. When he was diagnosed with dementia, it was a family heartbreak with unintended financial consequences. With no Power of Attorney, his children couldn’t alter his plans.

His estate plan went forward on his death and was subject to a much higher level of taxation than expected. Ewing says the man’s children could only watch as wealth that could have come to them disappeared.

The lesson from Ewing is to revisit your estate plans often and ensure they are up to date. As well, a Power of Attorney in place can help your family step in and make changes if you are unable to.

Have a strategy to prevent interference

Ewing has seen a fair amount of damage done by well-meaning but ill-conceived wealth and estate plans. She recalls one son thinking his father could avoid probate fees by selling his father’s property to himself for a dollar. The scheme backfired spectacularly. Ewing says that before wading into his father’s affairs, the family could have used some financial and tax advice from a private trust company which has expertise in exactly these areas.

Involving a private trust company can solve many financial and legal issues for people with cognitive decline, Ewing says. Since the trust company is legally acting on behalf of the individual, it works objectively to ensure the intentions in the Will are achieved or, in the case of a POA, that the directions in the documents are scrupulously followed so that the individual’s affairs and care are looked after.

As Susan dealt with her aunt’s affairs, she noticed her mother was having difficulties with her memory. But Susan’s experience allowed her to be more helpful. Her mother’s Will and Powers of Attorney are now in order. At 82, she has reluctantly given up driving and even has her own funeral arrangements made and paid for. The lesson for Susan was to be proactive in supporting her mom and ensuring her wishes would be fulfilled.

Susan says what happened to her Aunt Barbie’s health at the end of her life was a misfortune. Today we know more about what causes cognitive decline and how we can avoid it. Fortunately, avoiding a financial disaster may also be easier if we take the proper steps in advance.

DON SUTTON

MONEYTALK LIFE

ILLUSTRATION

DANESH MOHIUDDIN

- Lobo A, et al, Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology. 2000; 54 accessed May 13, 2022,

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Antonio-Lobo/publication/12464923_Prevalence_of_dementia_and_major_subtypes_in_Europe_A_collaborative_study_of_population-based_cohorts/links/561cae2d08aea8036724b53a/Prevalence-of-dementia-and-major-subtypes-in-Europe-A-collaborative-study-of-population-based-cohorts.pdf ↩ - Dementia in Canada, including Alzheimer’s disease, Statistics Canada, Sept. 21, 2017, accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/dementia-highlights-canadian-chronic-disease-surveillance.html ↩

- Lobo A, et al, “Dementia.” ↩

- Mortality from Alzheimer’s disease in Canada: A multiple-cause-of-death analysis, 2004 to 2011, Statistics Canada, July 12, 2017, accessed June 3, 2022, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2016005/article/14614-eng.htm ↩