My diet hasn’t changed, so why am I suddenly paying a lot more for groceries?

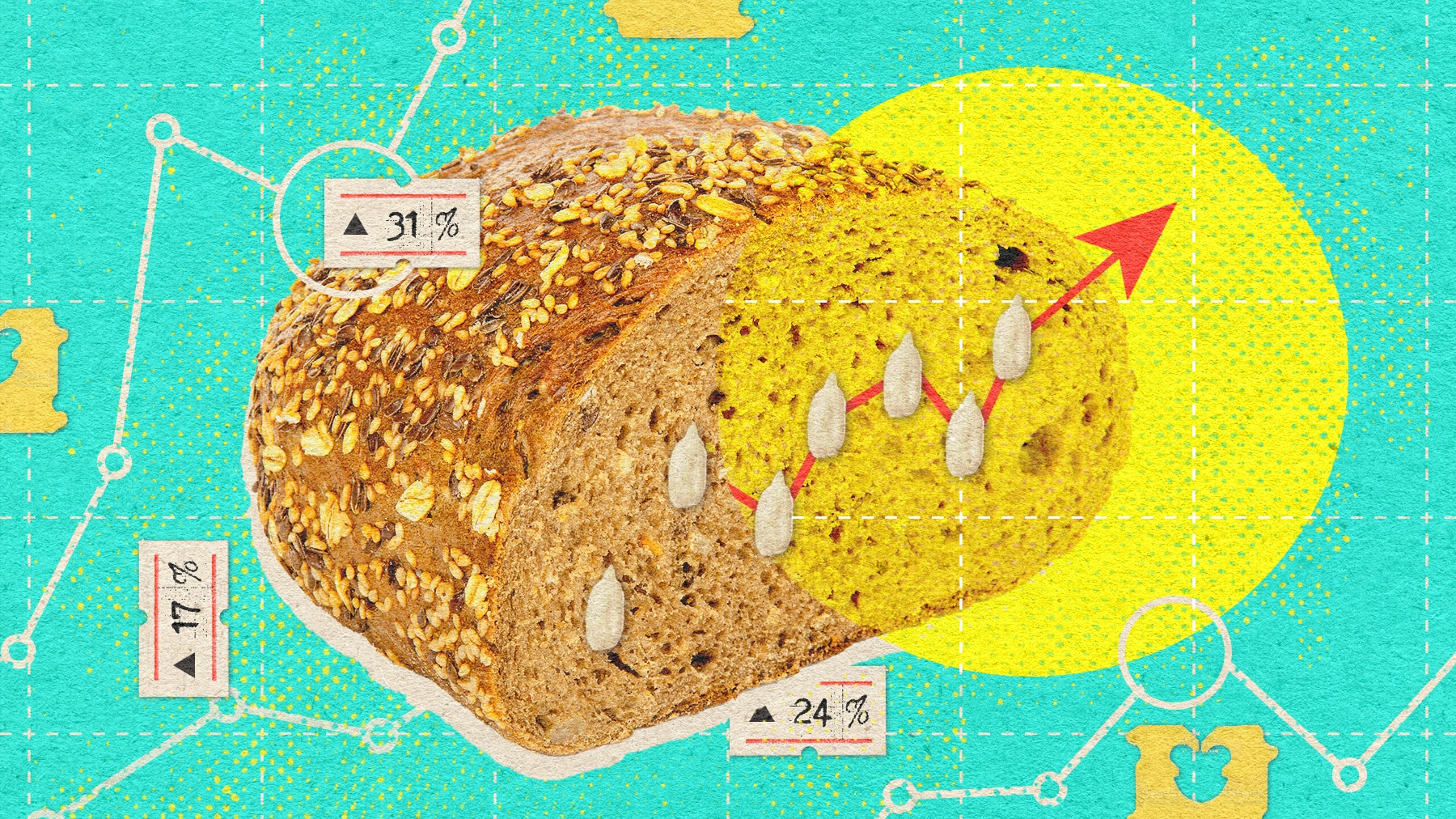

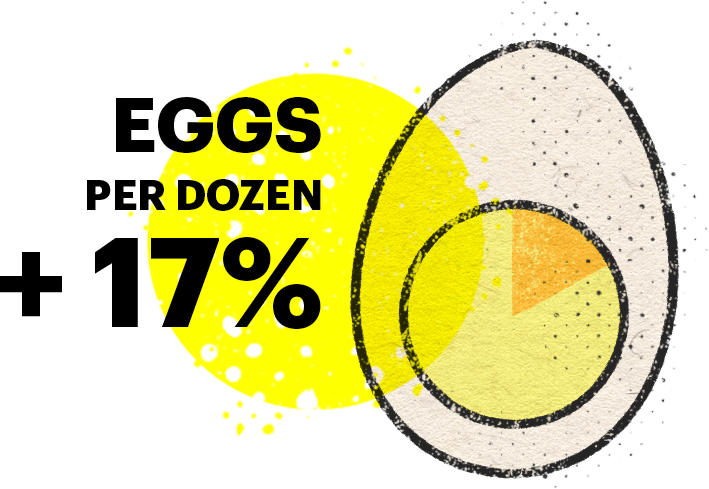

If you’ve been anywhere near the grocery store in the past year, you’ll know that a big part of the inflation surge we’ve seen in 2022 comes from food. Take bread: As of September, 2022, bakery products were 14.8% more expensive than a year earlier.

This is hardly an exclusively Canadian phenomenon. As of August, the cost of a loaf of bread in the European Union (EU) had risen 18% from a year earlier, according to EU agency Eurostat. In Hungary, bread was 66% more expensive. Not only does this hit us where it counts — our sandwiches — it hits our investments too.

The rise can be partly attributed to the Russia-Ukraine conflict that began in February 2022. In 2019, Ukraine and Russia together accounted for a quarter of global wheat exports, so any disruption to planting, harvesting and shipping in this Eurasian breadbasket would cause input prices for bread to rise.

Not only were civilians, including farmers, evacuated from areas near the front lines, but for several months, grain shipments were blocked from Ukrainian ports. Sufficient road and rail infrastructure to efficiently divert Ukrainian grain exports from sea to over-land do not exist. Meanwhile, sanctions curtailed Russian exports to western countries. In futures markets, speculators drove up the price of grain in anticipation of late deliveries, even before supplies began to dwindle.

When the price of one crop goes up, it affects producers’ choices, causing other crops to rise too. For instance, farmers in other exporting countries, such as the U.S., Canada and Australia, planted more grain than they might have before the invasion, thinking they’d make more money come harvest.

OK, I see how the conflict is causing prices to rise, but why can’t we just grow more wheat to offset the production losses?

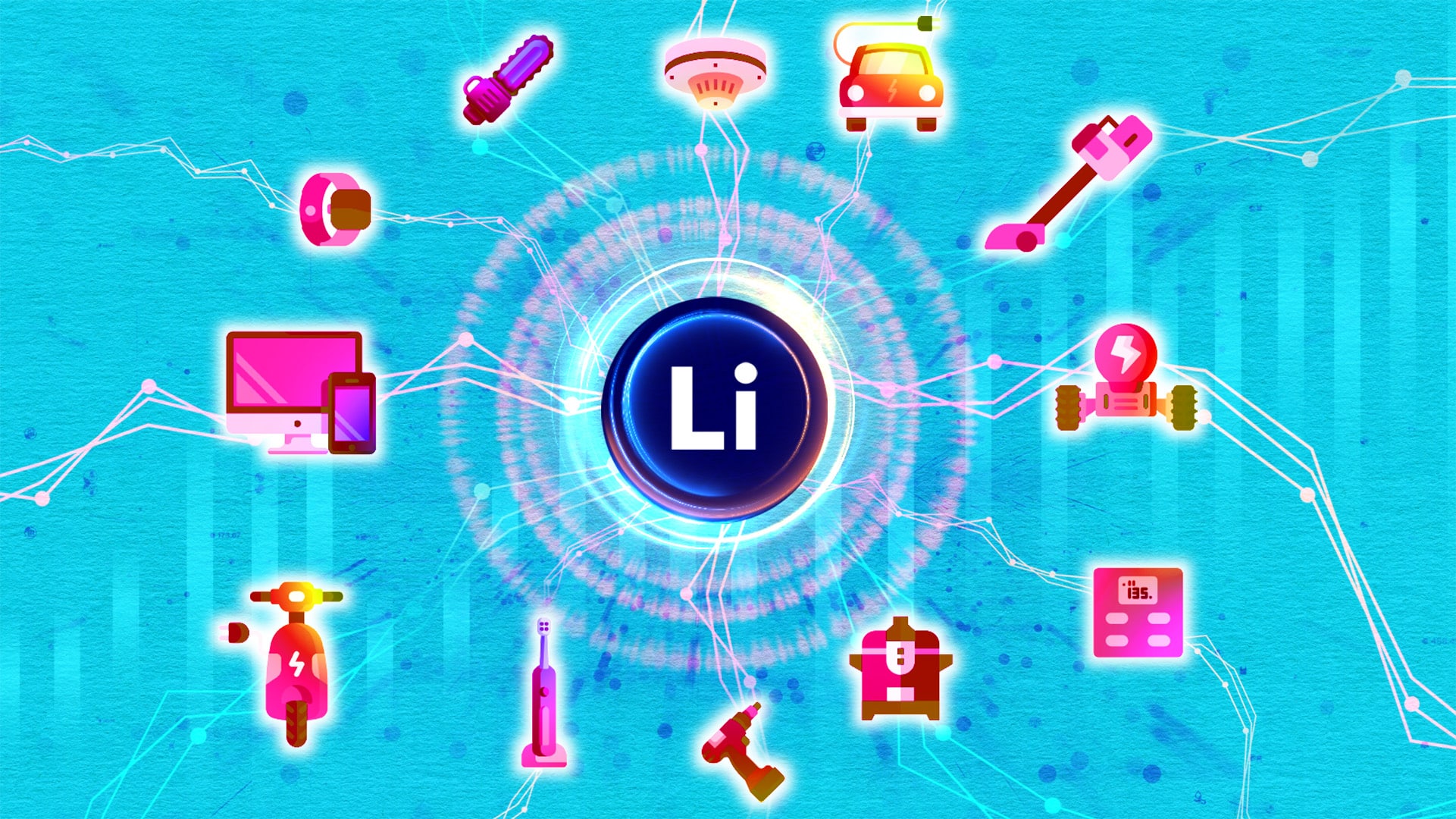

Apart from driving up costs for other crops, the conflict also affected demand for fertilizer. If you grow vegetables in your backyard, you can just treat your soil with organic fertilizer from a compost bin or a local livestock farm. But growing commodity crops on a large scale demands inorganic fertilizers that are mined and manufactured. For commercial farmers, fertilizer represents about 35% of the cost of growing wheat.

The fertilizer business is very different from the food business. It’s part of the highly cyclical materials sector, which encompasses the mining, forest and chemical industries. Whereas food is grown and processed by millions of farmers and businesses of all sizes, global fertilizer production is dominated by just a few countries and a small number of companies.

Russia and Belarus produced roughly 40% of the global potash supply before the Ukraine invasion. Both countries’ exports have been hit by U.S. and EU sanctions, as well as by their own export restrictions. Meanwhile, over the past year, China has imposed restrictions on exports of phosphorus and nitrogen fertilizers to conserve its own supply. China is the world’s largest fertilizer producer, but, as with the U.S., most of its output gets consumed within its borders. Of the roughly US$185 billion worth of fertilizer produced annually around the world, only US$55 billion is exported.

Canada, which exports US$5.2 billion in fertilizer per year, or roughly 38% of the global potash supply in 2021. As a nation we’re expected to meet some of the incremental demand required by the curtailment of supply from Russia and Belarus.

Why can’t other countries increase fertilizer production to meet demand?

The importance of potash in the production of fertilizer production can’t be overstated. Both potassium and phosphorus (two of the three ingredients necessary to produce fertilizer) are mined from potash and phosphate rock deposits. But potash mines themselves are huge, complicated operations. They’re also few in number. The opening or shutdown of a single mine can have a noticeable impact on global pricing, and it takes significant time to bring a new operation online.

Agriculture-focused nitrogen, the third key ingredient in fertilizer, is even more complicated to produce. It’s drawn out of the air and combined with hydrogen derived from natural gas to make ammonia, a critical component in nitrogen fertilizers. Natural gas also represents about 80% of the input cost for nitrogen fertilizers. Since 2020, natural gas prices have more than tripled. In response, European producers curtailed or even halted nitrogen production.

You might think a 15% hike in the price of bread is big, but the price of fertilizers fluctuates much more wildly. From September 2020 to April 2021, global potash prices more than doubled, surpassing US$1,000 per tonne for the first time since 2008, and peaking at US$1,210 per tonne in April. Prices have settled down somewhat since then, but remain well above historical averages.

Fertilizers are also bulky and have to be shipped great distances by ocean tankers, rail, trucks and barges. Transportation expenses represent a significant part of the input costs. Between rising transportation costs and the production of nitrogen fertilizers, the price of bread is in no small way influenced by the cost of fossil fuels.

Even though fertilizer prices have risen, can’t farmers justify paying the higher costs to boost their yield?

We saw earlier how rising wheat prices spurred farmers in countries far from the battlefields of Ukraine to increase their acreage and boost their fertilizer purchases. In this sense, fertilizer sales can be seen as a leading indicator of crop outputs — the more fertilizer sold, the more wheat will be grown this year, which ultimately might help bring down the price of bread. While fertilizer prices aren’t the only factor that affects the cost of food production, as a leading indicator they can be very a helpful clue — for investors and bread makers — in predicting crop production for a given year.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in the push-and-pull of commodity price volatility, farmers make choices that go both ways. Brazilian farmers cut their fertilizer purchases this year in response to the rising price. Even North American farmers have hit a point at which the economics of planting more acres of wheat no longer makes sense.

What can investors learn from this inflationary trend?

While no one wants to have to pay more for their sandwich at lunch or dig deep into their wallet to have a delicious croissant with breakfast, rising prices can benefit the companies that contribute to food production such as food processers, and packaging companies — and the investors who own their stocks. At the same time, bread and other foodstuffs are essential, almost recession-proof items, which means people will keep buying these items in any economic environment.

How could food inflation affect my portfolio?

The short answer: It’s hard to say. Much of it may depend on how the Russia-Ukraine conflict evolves and its impact on exports out of Europe. Since food itself is a household staple, major input costs for food, as well as other input costs like fertilizer, will likely remain highly volatile.

It will be important to consider whether rising inflation could introduce new geopolitical challenges that may impact your portfolio. While a 15% bump in the price of a loaf of bread may cause some budget shuffling for consumers in developed countries, it could have more significant consequences in developing nations, where food represents a greater share of household spending. Food inflation was a trigger for the Arab Spring uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East in 2011, for example.

Keep in mind that there are longer-term threats to the food supply chain than the conflict in Ukraine. Climate change and groundwater depletion in many parts of the world are increasing disruptions in crop yields. At the same time, ever more frequent and more damaging droughts and floods are also taking a toll on food security in many countries. While these are challenges, they will also create opportunities for investors as businesses step in to help fill the gap or invest in solutions to fight back against climate change.

Fertilizer companies have already seen a surge in demand as farmers look to boost their yields — and this can mean potentially higher stock prices. Between the impact of climate change on yields and the risk of geopolitical tensions on global food production, investors may expect new investment opportunities to arise from the agriculture sector, as producers innovate to boost their yield and contain costs by finding efficiencies, lowering waste and improving water management. Similar innovations will likely happen across the supply chain in terms of food processing, transportation and storage.

As an investor, being curious about these dynamics can help you form a view of different market sectors, whether they be food processors, fertilizer manufacturers, farm suppliers or even oil and gas producers. They all have a say in the price of a loaf of bread.