Investing after 70: Does your roadmap change?

Your 70s can be a pivotal decade for personal finances. After all it’s when most of us will begin withdrawing from our savings. But how does your investment strategy change? The answer may surprise you.

In 2014, Statistics Canada began polling Canadians 55 years and older about their income expectations heading into retirement. It asked, “would your income be adequate when you finally stop working?” Overwhelmingly, 86% of Canadians with post-secondary educations said, yes, they didn’t have worries.1

But as we all know it’s been a tumultuous decade thus far: COVID-19, inflation and international conflicts are just a few of the bumps we’ve encountered. Those polled are now in or near their 70s, and many will have crammed these years with intense decisions around retirement, health adjustments, perhaps downsizing and reevaluations of where to go from here. They may well ask, is it time for an investment reset?

Whether you’re investing because you have extra income and want to keep it working for you, or you have legitimate concerns about running out of money in retirement, you could be wondering what the best path forward is for you. Should you be less aggressive or more aggressive with your investments? And if you have never taken interest in your investments before, is now the time to wake up and learn about price-earnings ratios?

Kris Côté, a Certified Financial Planner with TD Wealth, says while the view at 70 may look much different now from your expectations, the fundamentals would generally stay the same.

“Planning for 70 starts about a half a decade earlier,” says Côté. “The changes that happen at 65 should all be in place by 70. You want to have a line of sight. You want to be prepared.”

“For example, if I’m meeting a client who is now age 70, neither of us would have heard of something called COVID-19 when they were age 65,” says Côté. “Some aspects of planning are stable and predictable, but you must make plans resilient to the things you can’t anticipate: Some things you can’t see that far in advance.”

"Planning for 70 starts about a half a decade earlier," says TD Wealth's Kris Côté

He says that means building flexibility into any strategy. A sound investment plan for this age should follow closely with what was put in place at 65, which in turn followed what happened at age 60. There should be little to no need to make abrupt changes because the continuity of your long-term financial plan — like one building block snapping precisely into the next — has been leading to this point in time, with a focus on preserving your wealth and moving you forward toward your goals.

If you are turning 70 soon and are still questioning how investments should be managed, here are some key areas to check out.

Assess your time horizon and risk tolerance

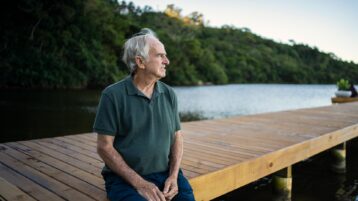

Concerns about money may not fade as you get older. In fact, the new financial environment you find yourself in, with no paycheque and mandatory withdrawals, may cause some unease because — is there a nice way to put it? — time is no longer on your side.

“If a person in their 50s has trouble managing their money, they may have trouble in their 70s as well,” says Côté. “Saving and investing is a learned behavior, it’s not something we’re born with and it’s not something where we magically gain wisdom at a certain age.”

He says investors who have been following an investment plan for years will likely have no reason to invest more aggressively: The flight path they have been on should have anticipated any eventualities, such as running out of money — a fear many people have. And if you haven’t been diligently planning, Côté says there are other means available, including examining monthly budgets to see if you can increase savings. Instead of turning to higher risk investments, Côté says adjusting your lifestyle to suit your goals could achieve the same results: A one-week excursion to Turks and Caicos, could be more cost-effective and just as rewarding as two weeks in Tahiti.

Have a plan for RRIF withdrawals

You must convert Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSP) into a Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF) or annuity by the end of the year you turn 71, and begin withdrawals the following year. That can be a conundrum for some: Save that money, invest it or just spend it? And what are the tax implications?

Côté offers some guidelines. If the RRIF is a primary source of income, naturally you’ll want to use it for your day-to-day expenses — that’s what it’s there for. However, if you or your spouse have a sufficient corporate or government pension, there may be several options available. Besides the obvious one of spending the money on yourself, it can be used to build up your Tax-Free Saving Account (TFSA) or a non-registered investment account, although each will have different tax consequences. For estate planning purposes, these funds can be used to make gifts to family members during your lifetime or even make charitable donations.

While the latter option can be a benevolent undertaking, it can also bring tax benefits, both to the person making the donation and to the charity that receives it. Giving money (or even investments) while you are alive, as opposed to giving through your Will, can be more tax-efficient, meaning more funds can be directed to your favorite cause. Needless to say, donating while you’re still on this earth also allows you to witness the good impact of your decision.

Explore tax outcomes

The unwinding of a RRIF comes with some tax consequences. As the funds you initially socked away in your RRSP during your earning years are withdrawn from your RRIF, the money will be taxed as income. The grand design of your registered savings plans now come into effect since your tax rate will presumably be lower at age 70 than when you were working.

As with other aspects of a financial plan, someone in their 70s should already have been following a tax strategy. For instance, it may have been smart, depending on your situation and income level, to begin withdrawing funds from your RRSP while in your 60s to balance the tax bill in later years.

You could also offset the tax owed by maximizing your investments in your TFSA. Other options could include taking advantage of income splitting with a spouse and charitable donation tax credits, as well as looking into other tax minimization strategies.

But strenuous efforts to reduce your tax obligation, without careful consideration, may cause more harm than good. “While minimizing tax is definitely something we should all be focused on, paying tax is a sign of having accumulated wealth. Don’t let tax be your only motivating factor when making decisions,” says Côté.

Manage your OAS and CPP

Considering your Old Age Security (OAS) and Canadian Pension Plan (CPP) as an investment that can grow with a little management might help clarify decisions around when to begin taking it. Unless you actually need the funds, delaying your CPP from age 65 until age 70, for example, allows it to grow by 0.7% per month to a maximum of 42%. To put this into context, there aren’t many other guaranteed ways to increase your money to that extent.

The catch is having a good idea about how long you will live: The above plan generally only works if you think you will live long enough to receive and use the money. If you think you will live into your 80s — statistics suggest many Canadians will — putting off your CPP for as long as possible makes a lot of sense.

For OAS, many people worry that the recovery tax — the so-called clawback — is worth reducing. OAS begins to be reduced when your net income hits a certain level: For the 2023 income year, it’s $86,912. Côté says there are several ways to reduce income and prevent the impact of the recovery tax. Yet he says people must keep in mind they should not do something premature just to out-maneuver the clawback.

Côté emphasizes that people should be careful with investing on their own and be sure to take into account multiple financial considerations. That means establishing goals and the resources to get there in the formation of the plan, not years after retirement. Once goals are made, investment targets, taxation strategies, financial and estate planning objectives tend to fall into place.

“Financial planners can help you consider what’s best for your situation or present you with a better path forward than you thought possible,” says Côté. “Without a plan, you are just guessing.”

DON SUTTON

MONEYTALK

ILLUSTRATION

DANESH MOHIUDDIN

- “Income in retirement: Expectations versus reality,” Statistics Canada, Dec. 13, 2022, accessed Sept. 25, 2023, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2022088-eng.htm ↩