Advanced probate strategies for wealthy Canadians

You may already know what probate is and how it works. But do you know some ways you can mitigate its impact when you pass wealth to your heirs?

Canadians with large and complicated assets should be mindful of the role probate has on their wealth. With fees or taxes potentially taking a considerable chunk out of an estate — for instance, a $1 million estate in Ontario would pay $14,500 — it may be a good idea to learn more on how probate works and how to mitigate its potential impact when your wealth transfers to the next generation. Fortunately, there are several strategies worth considering.

Treva Newton, a Tax and Estate Planner with TD Wealth in Victoria, B.C., says wealthier Canadians in particular stand to gain from a greater understanding of the probate process. Being an entrepreneur or an individual with extensive holdings or intricate family wealth means that assets may be more exposed to these fees and taxes.

“It’s a challenging process. Each type of asset is governed by different rules. You need to be careful how you plan,” she says.

Here’s a reminder of the role probate plays when you pass away and how to manage the costs for your heirs.

What is probate?

Probate is the court’s determination that a Will is the last Will and testament of the individual who has passed away. It certifies that the document is valid and that the executor has the right to manage the estate. This process begins shortly after an individual passes away: Before an executor can proceed with the management of the deceased’s assets and the transference of those assets to beneficiaries, financial institutions will request the Will be probated.

This entails a Will search to prove there are no other Wills and a valuation of the estate. Once the Will is probated, an executor can access bank accounts and other assets.

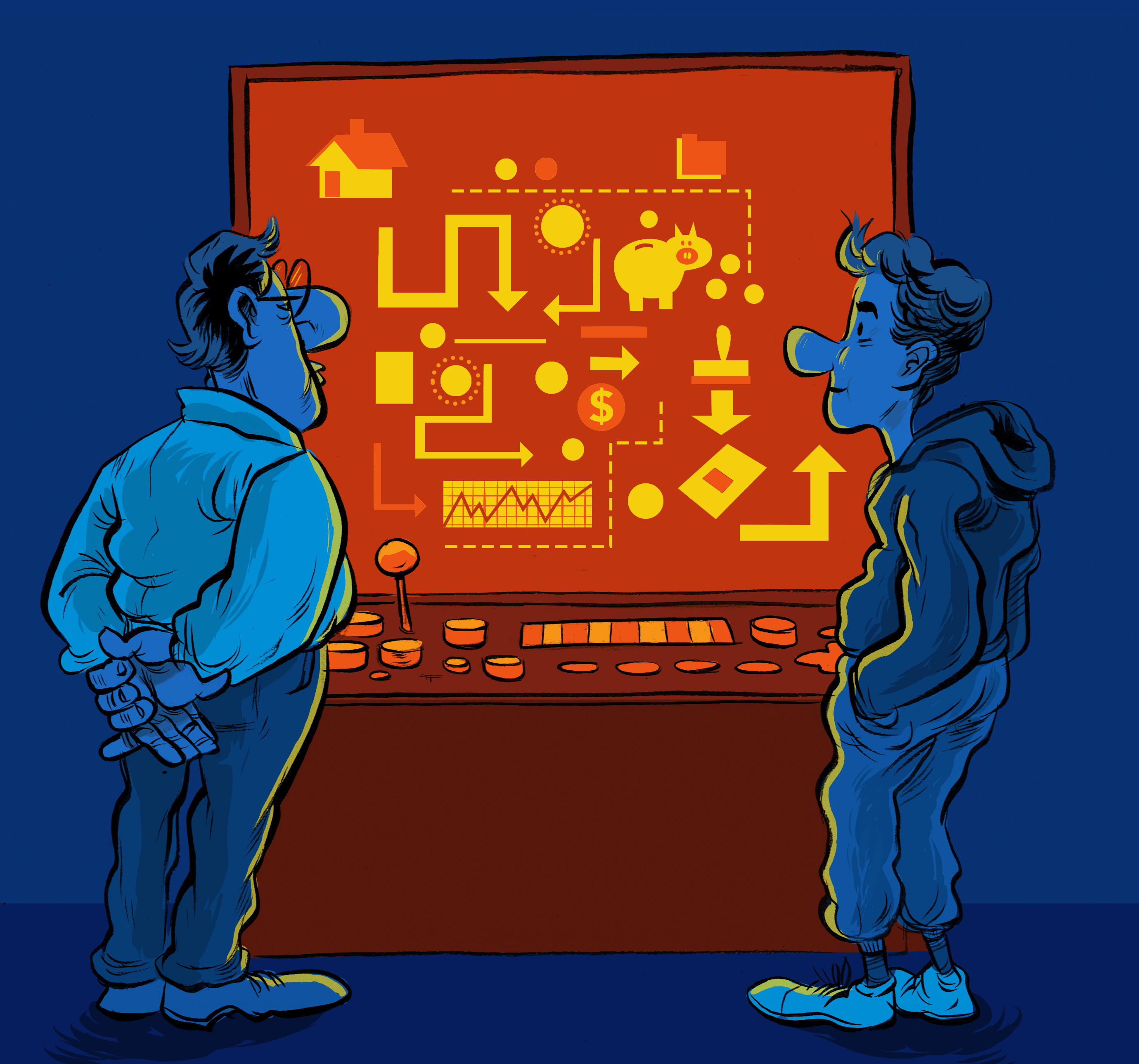

What assets do and do not go through probate?

Real estate, unless it is transferred through the right of survivorship, always goes through probate. But it is important to understand the role spouses can play in probate. If a couple own all their assets jointly (real estate or unregistered accounts) and if there are no other beneficiaries other than the surviving spouse, the assets will “roll-over” to that spouse, and the estate will be transferred without probate. When the second spouse passes away, (assuming the assets are in their individual name) then the estate will pass through the probate process.

Registered accounts such as Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs), Registered Retirement Income Funds (RRIFs) and Tax-free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) that have a named beneficiary are not considered part of the estate and will go directly to beneficiaries. Shares of a private company may also escape probate so long as they are the only asset of an estate being passed down and depending on what province you are in.

Costs and strategies around probate

While Manitoba and Quebec have no probate tax and some provinces have a flat fee, in Ontario and B.C. and other provinces, the costs are significant. Newton says you may have options available to you, particularly if you are a business owner, have diverse or complex financial assets, or an atypical family situation. For example, a Trust is often a solution that, despite legal expenses, may help to offset probate fees.

Put assets in a Trust. Putting funds and property into an Alter Ego Trust (in the case of an individual) or a Joint Partner Trust (in the case of a couple) is a popular method of reducing probate costs for wealthy Canadians.

“If you put assets into a Trust before you die, the assets won’t go through your will and won’t be subject to probate fees,” says Newton.

No taxes are triggered when transferring assets into an Alter Ego or a Joint Partner Trust unlike some types of Trusts. Alter Ego or Joint Partner Trusts are available only after an individual reaches age 65, with the key being that through this process, probate is avoided. Once the Trust is created, the individual or couple are the only people who can benefit from the income and use the capital of the Trust for the remainder of their lifetimes. When the individual or couple passes away, taxes are paid on capital gains earned on the assets being passed down. However, the Trust acts like a Will: Named beneficiaries receive the assets but probate is avoided.

A so-called family or discretionary Trust would work in a similar fashion although assets transferred to the Trust would be subject to capital gains tax. When the person who creates the Trust passes away, assets would pass to the beneficiaries without probate.

For people with multifaceted assets these Trusts may offer other benefits. For example, unlike Wills or the probate process, the Trust is not a public document and so may offer some privacy. If an individual believes their Will could be challenged by other individuals, having assets in the Trust instead of in the estate, could mitigate that worry.

Newton says while Trusts are attractive, individuals must be comfortable with the fact that once the funds enter the Trust, it is legally no longer their money — there may be complexities around shifting funds to family members.

There are costs and complications in setting up and managing any Trust. But she says they are useful for tax strategy purposes, outside of probate process, and can help families deal with complicated estate issues.

Have beneficiaries for registered accounts. While the funds in an RRSP or a RRIF can circumvent the probate process, that can only happen when there are beneficiaries named in the account. If there are none, the funds revert back to the estate and will be subject to probate. Everyone should check annually that the beneficiaries named in their registered accounts are up to date.

Couples should consider jointly-held ownership. In regard to couples, there may be no reason for a bank to ask for probate if all their assets are held jointly and everything passes to the surviving spouse in a Will. However, if each half of the couple has separate bank accounts and holds property in their own names or if there are other beneficiaries, a financial institution may ask for probate. Newton says that every couple’s situation is different, and there may be good reasons to hold assets individually: People can benefit from talking with their lawyer or a financial advisor.

Gift away assets. “Canada has no gift tax. If you don’t own the asset at your death, it’s not going to go through your Will. A lot of people will give away money and other assets during their lifetime if they feel they won’t require them,” says Newton.

These considerations could typically happen later in life when the amount of wealth someone accumulates is more than enough to see them through the rest of their days. A documented gift can also ensure funds given to a relative are not lost through a divorce or action by a creditor, and can also help to clarify intentions in a Will. Newton says that people should move carefully around gifting, for a variety of reasons: While we can make plans, we can’t really be certain what the future entails. If we give away too much money to family, unexpected surprises could happen, especially around healthcare costs, she says.

How can you prepare for the probate process?

Newton emphasizes that, while the probate process may be inevitable, that doesn’t mean people can’t work to alleviate some costs. Wealthy families may already be familiar with tax strategies and estate planning but a check-in with your tax lawyer, estate planner or Trust officer can clarify what steps to take during a generational wealth transfer. This can include what fees and services are required, what the tax impact will be and, ultimately, what the estate will look like after it is finally dispersed.

DON SUTTON

MONEYTALK LIFE

ILLUSTRATION

DANESH MOHIUDDIN