Is saving so much in cash a good idea?

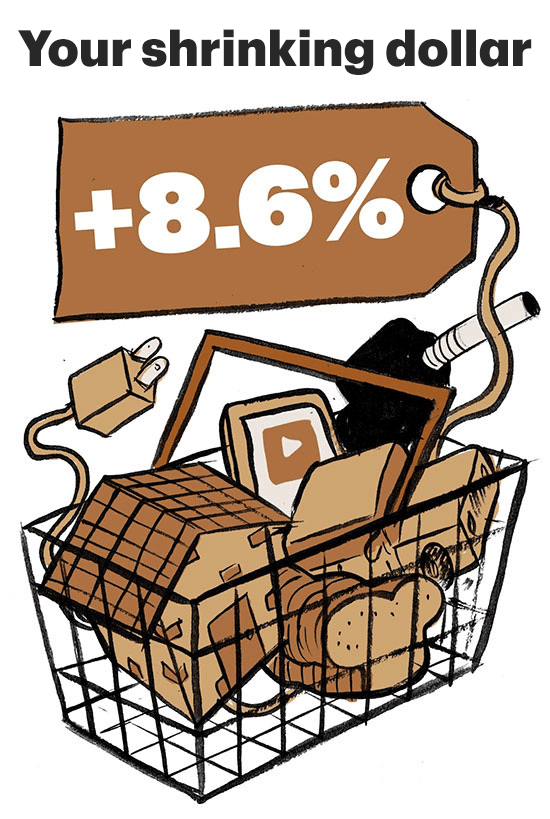

You might have heard the saying that saving is a virtue. But saving cash excessively may actually do more harm than good, especially during periods of high inflation.

When one of Natasha Kovacs’ clients sold a property they had inherited for $1.5 million, she thought of the many ways the money could help improve her client’s lives: new investments, paying off debt, a well-deserved trip somewhere.

Instead, they let the cash sit in a savings account.

And sit. And sit.

With inflation reaching historic highs throughout 2022 and interest rates on the rise, Kovacs — a Windsor-based Senior Financial Planner with TD Wealth Financial Planning — was extra mindful about how her clients’ situation could complicate their financial planning.

What happens to that cash just sitting there? “You’re guaranteeing yourself a loss,” says Kovacs. “When I say guaranteed, I mean that if cash is not growing, inflation will eat into its purchasing power.”

Unfortunately, we are seeing just how much inflation can hurt as everything from mortgage payments to asparagus prices rise. As Kovacs says, if you’re paying more for goods, but your savings are not keeping up, any sense of security you receive from having a healthy savings account balance may be false.

What Kovacs observed with these clients may not be unique. Many of us became savers during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the end of 2021, TD Economics reported that Canadians accumulated $300 billion in household net savings. 2 And while it’s hard to measure, financial institutions believe about $190 billion of that was excess savings — defined as savings that are above and beyond what consumers would have saved before the pandemic. Household savings peaked at 27% in the middle of the pandemic but since then, Canadians have resumed their spending habits. 3

But the big savers among us seem to be operating outside the trend: Kovacs says many high-net-worth Canadians who have their debt under control like to sock away cash in low interest accounts. Although she admits that having cash just idling in an account can offer people some reassurance, all that stagnant money may actually be doing more harm than good. The glow that comes with having cash stowed away dims if you don’t enjoy what that money can bring you or if you allow those savings to diminish.

But if so many of us are guilty of parking cash in savings accounts, why do we do it? What are we saving for?

Unless you have a good answer and a plan for that money, you may consider talking to a financial planner or advisor about what’s the best thing you could be doing for your financial goals with that cash.

That may be the logical thing to do. But, for many reasons, the urge to build up cash reserves is a strong one and not an easy habit to give up. Here are some ideas on what drives our urge to save and what we can do instead to help our savings grow.

Why do we save?

The relationship between saving and spending is a complicated one. For many of us, we’re warned about being reckless with credit cards from a young age and have heard that saving money is a virtue. To some, saving comes as second nature. But instead of spending frivolously, what if we are actually saving frivolously?

Kovacs says that our attitudes or behaviour around money can bring about our savings habits, with good and bad results: Fear of the future and the contentment derived from having money in their bank account are the two emotions she says that drive people to save.

She says this brings about the “what-ifs”: “‘What if we need new $7,000 electrical wiring? A new car, A new roof? What if we get sick or if the kids need money? What if there’s an emergency?'”

By internalizing these “what-if” scenarios and creating hypothetical expenses, Kovacs says we may be allowing fear to dominate us.

“People want to feel comfort. They always need a backup and cash in the bank gives them that. They feel in control,” she says. Family values around money may also dictate how we save. If, for example, sacrifices were made to pay the bills when you were a child, that attitude could make a big impression. Likewise, if you were a young adult struggling to pay bills, having extra savings later in life can give a feeling of security you never had.

Behavioural scientists have a phrase to describe the way our brains perceive the money we save versus the money we spend. They call it mental accounting or the jam jar theory. 4 When we separate our money into accounts — or even physical jam jars in our cupboards — we have the ability to form behaviours and rules around each of those accounts even if all the money is essentially the same. For instance, seeing savings grow might motivate some of us: “I saved $100 this month. Next month, I wonder if I can save $125?” But it can also produce boundaries for each account with faintly ridiculous results. For instance, we might actually run up a credit card bill to pay for car repairs rather than dip into a savings account we’ve earmarked marked for a vacation.

That’s because when we do mental accounting, what we are doing can become our primary focus and we may forget why it’s important. If we are saving for its own sake, without a plan in mind, we may miss an opportunity to take our finances to the next level. Mental accounting around savings may be why so many of us insist on keeping so much cash lying dormant in savings accounts — even when it’s not in our best interests.

Put a purpose to your savings

Kovacs offers this thought experiment: Look at your savings and ask to yourself why the money’s there. If you don’t have a good answer, it’s probably time to talk to your advisor.

“I ask my clients, ‘Walk me through what value you gain from the balance you have in your account.’ For me it’s a way to connect with them emotionally. It’s getting to understand all of their ‘what-ifs’ and then I can see what’s at the heart of their concerns — and then I help show them how to fix it,” she says,

Kovacs adds there’s nothing wrong with having some cash in a savings account for small, unexpected costs. And if you foresee a larger purchase in the immediate future, for sure, park the cash there until you need it. It can be a great idea, for example, to put some investments in a Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA) where it can grow but also be easily accessible with no tax considerations if you need to yank it out to get the plumbing redone. Beyond that, she tells her clients: “If you tell me making money is important, let’s get your money working for you.”

No matter why you might be over-saving, Kovacs has some thoughts on some things you can do with any excess cash.

What to do with excess savings

You can start by working with your financial planner in developing a strategy that is personalized for you. This can include discussing not only lifestyle goals you want to pursue, like travel or a great golf membership, but also financial plans that can actually help bring you some comfort, like investing or tax and estate planning.

What happened to her clients with their $1.5 million windfall? It took a while but eventually Kovacs persuaded them to energize their money.

“They said they had a lot going on, but I pleaded, ‘This [sale] is a life change. There are tax efficiencies that will be required, and we have your children to factor in. And that all takes times to sort out with joint meetings with accountants and lawyers,'” she says.

She eventually convinced them to develop a solid financial plan that centred on a move toward semi-retirement. The plan included setting money aside for their kids’ education and to help them get into the housing market, as well as an investment strategy to help cover the couple’s own long-term health care costs if needed in their old age.

Other people may have different needs. No matter what your circumstances and priorities may be, moving savings into a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP), a TFSA or even a non-registered investment account can mean idle money has a chance to grow through investments such as mutual funds or stocks and bonds. The growth of savings not only helps offset inflation, but it can give you a bigger nest egg and a wider scope for future plans — particularly as compound interest works on building your accumulated funds over time.

But there may be other considerations. If your children are the beneficiaries of your RRSP or even your cottage, they may be looking at a large tax bill when the assets are transferred over. Kovacs says, in this case, there are several options people can consider to help ensure their children’s tax burden is eased. She says, even if the tax or financial consequences of these events happen far in the future — perhaps even after you have passed — directing cash to these areas now may actually save more money for your family in the long run.

As well, many people have causes or charities in the community they’re passionate about. Kovacs says making donations or even setting up your own foundation can be a surprisingly inexpensive way to make a difference. She says financial planners can help individuals rationalize their savings by helping them put extra money to work, build a better plan and open doors to opportunities that were previously thought to be closed. Ultimately, Kovacs says having some money in a savings account is great but there are often better things to concentrate on: “I try to help clients to refocus on the balance of what life is meant to be for them.”

- Utilities, food, entertainment, shelter and transportation cost the average Canadian family $50,976 in 2019. The cost rose to $55,777 in 2022. Source: Statistics Canada. ↩

- Sri Thanabalasingam, Excess Household Savings and Implications for Inflation in Canada, TD Economics, Nov. 3, 2021, accessed Aug. 19, 2022, economics.td.com/ca-excess-saving ↩

- Stephen S. Poloz, “Canada’s Economy and Household Debt: How Big Is the Problem?” Bank of Canada, accessed Sept. 19, 2022, www.bankofcanada.ca/2018/05/canada-economy-household-debt-how-big-the-problem/ Current and capital accounts – Households, Canada, quarterly, Statistics Canada, accessed Sept. 19, 2022, www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610011201&pickMembers%5B0%5D=2.1&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2019&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=04&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20190101%2C20220401 ↩

- The jam jar theory of finance, MoneyTalkgo.com, June 17, 2019, accessed Aug. 22, 2022. www.Moneytalkgo.com/video/the-jam-jar-theory-of-finance ↩